The Chesapeake watershed, including most of Maryland, Virginia, and Delaware, plus even parts of West Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, and the real swamp, Washington DC, through the James, York, Rappahannock, Potomac, Paturxent, Patapsco, Susquehanna, Pocomoke, Wicomico, Nanticoke, Choptank, and Chester (that was a mouthful!) rivers, has long been carefully watched and managed.

Likewise, with the abundance of people, livestock and agriculture existing in the Green Bay watershed, this area is being looked at with wary eyes. Though not nearly as large as the Chesapeake, the Green Bay watershed contains parts of Northeastern Wisconsin and Southern Upper Michigan and four (much easier to pronounce) rivers. They include the Fox, East, Pensaukee (whoops, snuck one in there) and Oconto rivers.

The main agricultural elements which flow into the watershed and ultimately the Green Bay (the water, not the city!) are nitrogen and phosphorus. An interesting trial was conducted on farms in the Green Bay watershed, ostensibly to determine the nitrogen guidelines for various “alternative” forages to be included in UW crop recommendation brochures. The term used was Economic Optimum Nitrogen Rate or EONR. However, the trial also demonstrated some important qualities of modern forage grasses.

The trial was conducted by John Jones, Ph.D., CCA, Dept of Soil Sciences, Francisco Arriaga, Ph.D., Dept of Soil Sciences, and Kevin Jarek, M.S., Extension Educator. All are associated with the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the research was partially funded by the Midwest Forage Association (MFA).

The trial started with the 2021 crop year and continued through 2022 and will be completed after the 2023 crop is summarized. So far, the first two years were summarized by Dr. Jones. One of the crops planted was our Dairynax, a cocktail mixture of mostly Italian Ryegrass (IRG) plus 6.45% each of hairy vetch, Berseem red clover and medium red clover. This is a crop which we recommend planting in the early spring, but in the 2022 trial was planted much later due to—guess what—weather! If the cocktail mixture contains BMR sorghum-sudan (Yieldmax), then planting dates must be after soil temperatures reach 60◦F and rising. However, a mix with IRG and legumes can be planted in the Upper Midwest as soon as you can get on a field without the tires cutting in.

The Trial and Methods – Dr. Jones’ Abstract

The experimental design consisted of seven N fertilization rates replicated 4 times, using a randomized complete block design. Nitrogen rates were changed from 2021 to 2022 so that a wider range of rates could be used, and the experimental parameters correctly bracketed a potential optimum N rate. Thus, in 2022 eight N rates were used. Plot size was 10 by 40 feet. At each site, the seed bed was prepared, and the forage planted. Just prior to planting, soil samples were collected from 0- to 6-inch depth in each replication (1 core per plot composited by replication) and analyzed for pH, buffer pH, and Bray-1 P and K. Samples were also collected from the 0- to 12-, 12- to 24-, and 24- to 36-inch depths in the no N control plot (3 cores composited per plot) and analyzed for nitrate-N. Nitrogen fertilizer treatments were broadcast as SuperU immediately following first, second, and third cutting.

The plots move each year to another field on the same farm. A farm was utilized on the west side of the watershed (Daniel Olson’s farm ) and one on the East.

The Unintended Findings

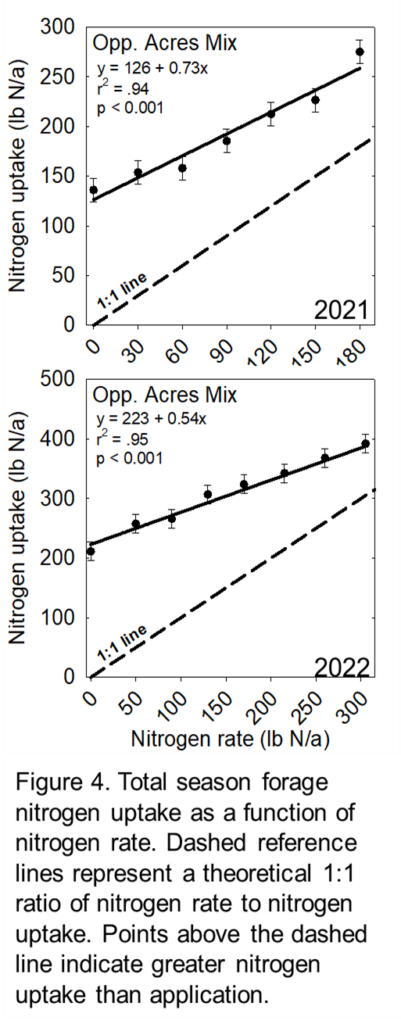

So, what was the important, but unintended discovery of this trial? Appended near the bottom of the UW trial summation was the Figure 4 which showed the uptake of N compared to the applied amount. In each year and at each level of applied nitrogen.

The cocktail mix utilized more N than was applied. The dashed line indicates the one-to-one relationship of N applied (from 0 to 300 pounds!) and N utilized by the forage. This indicates the N both captured and utilized was greater than the N applied, even at the 300#s N rate.

When a cocktail mix follows corn there typically is N which was not used effiently by the corn. Corn roots are not as effective as grass roots in gobbling up the N.

Benefits of N Effiency

The complex root systems of grasses utlize N effeciently and quickly, and is the main action which keeps nutrients in the field and out of the watershed. Furthermore, having a constant crop which will accept nutrients is a huge benefit for dairies.

Grasses will take up even more N, however, the result will be higher levels of soluble crude protein than is normal with grasses in the 16 to 20% CP range which will be more on the bypass protein side of the equation. Grasses which do attain 23-24% CP will be more like alfalfa at the same CP (soluble).

Always sulphur (at the rate of 1 to 10 S to N) is needed for grasses to convert N to protein. Usually, with manure, the need is fulfilled. If using purchased fertilizer, AMS should be part of your mix.

Our recommendations are, as much as possible, follow a corn crop with a grass (and sorghum-sudan cocktail mix for the symbiotic relationship between the two crops. The cocktail mix utilizes N which the corn leaves behind and also provides a better soil condition in which to grow corn—even exceeding to standard first-year corn benefit. These benefits include natural rootworm and weed preventions.(See Why Following Sorghum-Sudan with Corn is such a Good Idea).

Well, what about the trial?

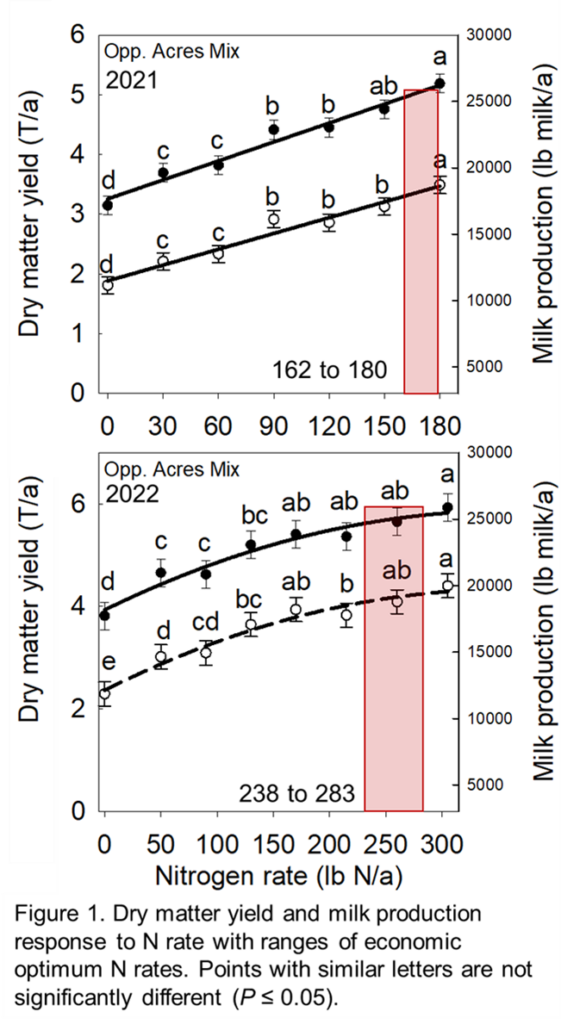

The reason for the trial again was to determine the EONR levels comparing forage value attained and N expended. The two years of the trial were very different—2021, dry, and 2022 wet. In other words typical Wisconsin weather! And so were the values for the EONR. See the results in the chart below. It looks like according to this trial, our age-old recommendations for N of 25 lbs. per DM ton of forage which has seemed to be effective may need to be bumped up to 30 lbs especially in wet years.

Yields in the trail at the EONR (pink area in the chart) were about six tons DM per acre with one cutting each year not summarized. These are pretty comparable yields in this area (just below the Arctic Circle!) and with late planting especially in 2022.

And lastly, what about the utilizing the phosphorus?

The P issue is dicussed in the Grass Report (available from our forageinnovations.guru website). But suffice it to say, although grasses do not luxury feed on P, but it does percentage-wise contain higher levels of P than legumes or corn. So the combination of P% and yield make forage grasses the best plant to mitigate P excesses.

To further discuss how we use grasses, both warm- and cool-season in dairy diets or any other forage questions, you can reach out to Daniel at daniel@forageinnovations.guru or me at 608-516-0101 or larry@forageinnovations.guru. Also, you can find much information on either the Forage Innovations Facebook or YouTube pages